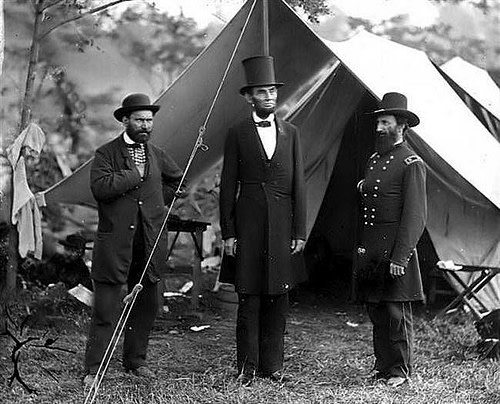

Not many people know that Abraham Lincoln wasn’t his party’s first choice as their Presidential nominee. The Republican field was stacked with candidates far more accomplished and better known than the circuit lawyer from a backwater frontier state, but Lincoln somehow secured the Republican nomination and then the Presidency. Immediately thereafter, the Illinoisan did something extraordinary: he formed his cabinet from the same Republican luminaries who had been his rivals for the nomination. One of his most important posts, the Secretary of War, went to one of Lincoln’s most bitter adversaries, Edwin M. Stanton, a man who had previously served as the Attorney General of the United States.

Interestingly enough, this was not Lincoln’s first close encounter with Stanton. The future President had worked with his future War Secretary six years prior, as a fellow lawyer on a joint case in Ohio. It was not an auspicious beginning. Stanton refused every meal invitation and would not even walk to the courthouse with Lincoln, later commenting to a friend that the future President looked like a “d—ned long armed ape.” After being appointed Secretary of War, Stanton began to work busily at cross-purposes with his Commander-in-Chief, routinely disobeying orders he considered ignorant or shortsighted.

One day, a congressman arrived at Lincoln’s office, reporting that the Secretary of War had not only countermanded a direct order from Lincoln but also called the President a d—nd fool for issuing it.

“Did Stanton say I was a d—nd fool?” asked Lincoln.

“He did sir, and repeated it,” replied the congressman.

This accusation was no small thing—Secretary Stanton was guilty of mutiny. Lincoln’s response reveals volumes about his character:

“If Stanton said I was a d—nd fool, then I must be one, for he is nearly always right, and generally says what he means. I will step over and see him.”

There are very few people in Lincoln’s situation—brand-new, confronting a national existential crisis— who would have responded similarly. However, Lincoln was known for a singular quality: humility. This virtue allowed Lincoln to build one of the most talented Cabinets in America’s history by freeing him from his wounded pride and thus enabling him to make the best use of the best people. Eventually, Lincoln would earn the steadfast loyalty of his team—Stanton came to call the President “the best of us”—and that team, under Lincoln’s leadership, would shepherd America through arguably the darkest time in the country’s history. None of this would have been possible had Lincoln not been humble.

WHAT HUMILITY IS NOT

Despite its critical importance for leaders, the virtue of humility is neither well understood nor widely sought after. In many ways, leaders, especially business ones, are expected to be larger-than-life figures gifted with superior abilities and marked by few, if any, normal human failings that humility would acknowledge and reveal. The CEO of Gree Electronics, an air conditioning giant, summed up this philosophy of larger-than-life leadership in a pithy self-assessment:

“I never miss. I never admit mistakes, and I am always correct.”

But the non-humble are not flawless; rather, they hide their weaknesses until poor choices compound to a point that the truth can no longer remain hidden. Consider, for example, the politicians who trumpet their family values one day only to be caught involved with prostitutes the next. If we want to avoid the fate of leaders turned laughingstocks, then we cannot hide our failings behind a façade. We have to confront them, both with ourselves and with others.

Because this virtue is so widely misunderstood, it is easier to begin our exploration of humility by identifying what it is not. Humility is not thinking less of ourselves and downplaying our gifts and talents. It is not denying that we are good at certain things, or that we have done good work in certain areas. It is not spending inordinate amounts of time obsessing about what we do wrong every day. However, many of us think that these things are precisely what are meant by this virtue, which gives this character trait a weak, even neurotic, overtone.

Another prevalent misconception about humility is that it is perfectly acceptable to be internally proud of strengths and accomplishments, but the moment the internal becomes the external, the humble virtue vanishes. We have to turn away from all praise, no matter how well meaning. We have to put on false modesty and lie to others. Humility thus becomes a virtue of the deluded or the deceitful.

When we tag the above maladies with the label humility, which is common, then our experience with those who practice this “virtue” only reinforces our negative perception of it. Not only is it misunderstood—it is often confused with vice.

TRUE HUMILITY: A LEADERSHIP ACCELERATOR

So what exactly is humility? At its core, humility is nothing more than a realistic view of ourselves and our relationships combined with an accurate appraisal of our teams and how they view us. There is a story about Oliver Cromwell, the famous seventeenth century English general, that neatly sums up this concept. At the age of forty-four, Cromwell had overthrown the British monarchy and had become the most powerful military and political figure in England. In 1654, this luminary sat for a picture, and the intimidated painter turned out a first draft depicting Cromwell as an idealized Roman god. Cromwell took one look at the painting and rejected it out of hand, for the painter had omitted some noticeable facial blemishes. Cromwell demanded the painting re-done, realistically, and this time he had some guidance for the painter.

“You will paint me just as I am—warts and all,” he said, and thus bequeathed to the English-speaking people a phrase that neatly sums up the concept of humility: “Just as I am, warts and all.”

Why is humility, properly understood, so important for a leader? First, this virtue serves as a necessary counter-balance to a driving sense of mission. Few people choose to advance causes that they believe are inherently evil. Even the monsters of history—Stalin, Hitler etc.—started with what they truly believed were worthwhile causes. And that is precisely the problem with passionate leaders who pursue their mission without humility. They risk destroying that which they would save. For example, to create a society characterized by liberty, equality, and fraternity, French revolutionary leader Robespierre beheaded thousands of his fellow citizens.

A humble leader, however, is far less likely to take their mission to immoral, illegal, or illogical extremes, because the humble leader is far more likely to hold a balanced view of themselves and to surround themselves with people who will help them hold such a view. “Faithful are the wounds of a friend,” says the book of Proverbs, “but the kisses of an enemy are deceitful.” Humble leaders enable and encourage their trusted friends to wound them.

Humility also accelerates the pace at which we learn from mistakes, which speeds the pace of learning and innovation. Everyone makes mistakes, and leaders typically make more than most—after all, they have increased scope for decision-making. Humility enables a leader to confront and admit their mistakes quickly—to fail in small ways rather than large ones. It also allows the best ideas of an organization to bubble up to the surface. If a team feels that their leaders will take input from everywhere, then that team will be much more likely to float their ideas in the hopes of having them enacted.

Thus, the “soft” virtue of humility has some very “hard” practical consequences. Organizations will find that the rate at which they produce ideas and products significantly accelerated. They will be able to iterate and innovate more quickly than competitors. At the individual level, humility allows us to strengthen personal connections with our teams by acknowledging openly that we are real people with real problems. And last but not least, humility allows us to make big decisions, for it frees us to take responsibility for failure.

Many people know that General Dwight Eisenhower led the famous D-Day invasion of continental Europe in 1944. Few know that on June 5, 1944 (the Eve of D-Day), General Dwight Eisenhower pinned the following note: “Our landings in the Cherbourg-Havre area have failed to gain a satisfactory foothold and I have withdrawn the troops…The troops, the air and the Navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault attaches to the attempt, it is mine alone.”

Eisenhower’s humility prepared him to shoulder the responsibility for the failure of D-Day, which, in turn, gave him the freedom to order the invasion of Normandy under conditions that were far from ideal. The seas were choppy, the air was foggy, and the invasion date had been twice delayed due to weather. A lesser man might have hesitated, too proud to risk the opprobrium associated with a blighted effort. Eisenhower did not. The rest is history.

True leaders are not one-in-a-million celebrities, nor are they special, gifted people on a plane apart from the rest of humanity. Rather, they are every day people who realize their own flaws, accept correction and seek to learn from those around them. If we can attain humility, then we can be assured that we have gained a character trait that will help us lead well in the long run. As we think about whether we are developing this virtue, we can ask ourselves a few questions to get started:

When was the last time we said, “I’m sorry, I was wrong, will you please forgive me?”

-To our team at work?

-To our friends?

-To our spouse?

-To our children?

When was the last time we asked for constructive criticism?

-From our teams?

-From our friends?

-From our family members?

Humility is not an easy virtue to cultivate, it requires that we deliberately make ourselves vulnerable to others. And our pursuit of it must never cease—the moment that we think we have arrived is the moment in which this virtue disappears.

**Donovan Campbell is a Management Consultant, author, speaker, and served three combat tours with the United States Marines. His second Iraq tour is chronicled in the NYT best-seller, Joker One. Newsweek named Joker One a top war book of the decade. His book, The Leader’s Code is scheduled to launch on April 9, 2013, and highlights the six attributes of character, including humility. Donovan believes character is the basis for leadership, and we agree. To learn more about Donovan and his book, visit www.theleaderscode.com.

**

For assistance with strategy and leadership initiatives, please contact us.

Contact Us

Ready to achieve your vision? We're here to help.

We'd love to start a conversation. Fill out the form and we'll connect you with the right person.

Searching for a new career?

View job openings